We’ve moved!

Please click here and bookmark our new location:

Filipino officials and Japanese General Homma Masaharu at the former residence of the U.S. High Commissioner, January, 1942

In October, 2013, the country will mark the 70th anniversary of the so-called Second Republic established under Japanese auspices.

In anticipation of that event, the project aims to complete the publication of the Iwahig Prison Diary of Antonio de las Alas, a prominent prewar political and business figure, and member of the Laurel government. His diary, written while he was detained by Allied forces awaiting trial for collaboration, gives a thorough account of the dilemmas and choices made by officials who served during the Japanese Occupation, including their motivations and justifications for remaining in the government.

The diary of de las Alas goes backward and forward in time: starting on April 29, 1945 he details the tedium and petty bickering of prison life, he also gives an insight into politics and society during the Liberation Era, while extensively recounting his experiences during the Japanese Occupation.

Salvador H. Laurel, son of occupation president Jose P. Laurel, was tasked by his father to keep a diary of their going into exile at the hands of the Japanese (see entries from March 21, 1945 to August 17, 1945).

His account bears comparison with the conversations recorded by Francis Burton Harrison, prewar adviser to President Quezon, who again served as an adviser during World War II, when the Philippine government went into exile in Washington D.C. His entries covering the government-in-exile begin on May 30, 1942, and come to an end on May 31, 1944.

In the Philippine Diary project, other diarists put forward different facets of life in the Philippines during the Japanese Occupation.

Charles Gordon Mock, an American originally imprisoned together with other Allied civilians in the University of Santo Tomas, details his experiences as a prisoner-of-war transferred to Los Baños on May 14, 1943.

The experiences of soldiers and guerrillas are captured in the diary entries of Ramon Alcaraz –his entries chronicle the transformation of a prisoner-of-war into a soldier serving in the Japanese-sponsored Philippine Constabulary: and how he used his Constabulary postings for guerrilla activities (the progression of this development can be gleaned from a sampling of entries: June 30, 1942; August 3, 1942; August 30, 1942; February 20, 1943).

The diary of Felipe Buencamino III ends with his first few weeks as a prisoner-of-war in the concentration camps established by the Japanese; but he resumes his diary on September 21 1944, at the tail end of the Japanese Occupation (see October 2, 1944 for an example of the growing anticipation of the end of the Occupation): in fact, his diary ends just at the moment of Liberation.

His father, Victor Buencamino, chronicles the frustrations, fears, and tedium of being a mid-level official still serving in the government, not so highly-placed as to be ignorant of public opinion, but also, trapped between public opinion and his own problems as someone in government. His diary serves as a counterpoint to the diaries of soldiers and officers in the field, and to the other diaries describing life during the Occupation.

Two other diaries remain to be uploaded extensively, namely the Sugamo Prison diary of Jorge B. Vargas, onetime Chairman of the Philippine Executive Commission, and Laurel’s wartime ambassador to Japan, and the diary of Fr. Juan Labrador, O.P, a Spanish Dominican who kept a diary during the Japanese Occupation. But perhaps these will have to wait for future anniversaries.

You can browse the entries of the diarists mentioned above by clicking these links to view their entries in reverse chronological order:

Victor Buencamino (second from left, second row), with his family in the Pines Hotel, Baguio, 1932. Rightmost on second row is his eldest son, Felipe Buencamino III.

The Philippine Diary Project includes the diaries of a father and his son: Victor Buencamino, and Felipe Buencamino III. At the outbreak of the war, Victor Buencamino was head of the National Rice and Corn Corporation, precursor of today’s National Food Authority. His published diary covers the period from the arrival of the Japanese in Manila, and the first half of the Japanese Occupation.

His diary provides an in-depth look into the dilemma facing government officials who stuck to their posts despite the withdrawal of the Commonwealth Government and the occupation of the Philippines by the Japanese. At certain points, particularly from January-April, 1942, he gets intermittent news about his son (who was, on the other hand, participating in clandestine military intelligence missions, even in Manila).

Particularly gripping are his entries for April, 1942, when on one hand, he is wrestling with increasing Japanese interference and intimidation –including his being summoned to the dreaded Fort Santiago, where other members of his staff had already been summoned and in at least once instance, tortured– and on the other, frantic for news about his son, particularly after the Fall of Bataan, when on the same day he received condolence messages and news his son was alive. Then, he recounted the grief of parents and his own search of the concentration camps.

As for Victor Buencamino’s son, Felipe Buencamino III, known to his friends as Philip, was a young journalist who became a junior officer in Bataan, assigned to General Simeon de Jesus and his military intelligence unit. He kept a diary from the time of the retreat of USAFFE forces to Bataan, conditions there as well as in Corregidor, which he periodically visited, looming defeat, the eve of surrender, and then the Death March and the ordeal of his fellow prisoners in the Capas Concentration Camp, as well as his classmates. At times, his diary intersects with other diaries, such as the diary of Gen. Basilio J. Valdes, since Philip accompanied the General during one of his visits to the front. He resumed his diary, briefly, in 1944.

A close friend of Philip, Leon Ma. Guerrero, who was mentioned many times in Philip’s wartime diary, wrote about Mrs. Quezon and the ambush in which she was killed, in 1951. In his essay, he also wrote about his friend, Philip:

In Bataan I shared the same tent with Philip Buencamino, who was later to marry Nini Quezon. He was the aide of General de Jesus, the chief of military intelligence, to which I had been assigned. I remember distinctly that one of the first things Philip and I ever did was to ride out in the general’s command car along the east coast out of pure curiosity. The enemy’s January offensive was turning the USAFFE flank and all along the highway we met retreating units. Then there was nothing: only the open road, the dry and brittle stubble of the abandoned fields, and in the distance the smoke of a burning town. We turned back hurriedly; we had gone too far. I am afraid we never got any closer to the front lines. Our duties were behind the lines. We were quite close during the entire campaign until I was evacuated to the Corregidor hospital, and I developed a sincere admiration for Philip. He was a passionate nationalist who could not stomach racial discrimination, and I remember him best in a violent quarrel with an American non-commissioned officer whom he considered insolent toward his Filipino superiors.

On April 28, 1949, Felipe Buencamino III, together with his mother-in-law, Aurora A. Quezon, sister-in-law, Maria Aurora Quezon, and Ponciano Bernardo (mayor of Quezon City) and others, were killed in an ambush perpetrated by the Hukbalahap. The late Fr. James Reuter, SJ, wrote about it in 2005:

On April 28, 1949 – 56 years ago, Doña Aurora Aragon Quezon was on her way to Baler. With her eldest daughter, Maria Aurora, whom everyone called “Baby”. And with her son-in-law, Philip Buencamino, who was married to her younger daughter, Zeneida, whom everyone called “Nini”. Nini was at home with their first baby, Felipe IV, whom everyone called “Boom”. And she was pregnant with their second baby “Noni”.

On a rough mountain road, in Bongabong, Nueva Ecija, they were ambushed by gunmen hiding behind the trees on the mountainside. The cars were riddled with bullets. All three of them were killed. Along with several others, among them Mayor Ponciano Bernardo of Quezon City.

Adiong, the Quezon family driver, was spared. Running to the first car, Adiong found Philip lying on the front seat, his side dripping blood. Philip smiled at Adiong and said: “Malakas pa ako. Tingnan mo” — “I am still strong. Look!” And dipping his finger in his own blood, Philip wrote on the backrest of the front seat: “Hope in God”.

When they placed him in another vehicle for Cabanatuan, his bloody hands were fingering his rosary, and his lips were moving in prayer. This was consistent with his whole life. His rosary was always in his pocket. And on his 29th birthday, exactly one month before, on March 28, 1949, at dinner in his father’s home, he said to Raul Manglapus: “Raul, the Blessed Virgin has appeared at Lipa, and has a message for all of us. What are we going to do, to welcome her, and to spread her message?”

He was echoing the thoughts of Doña Aurora, who wanted a national period of prayer to welcome the Virgin and to spread her message of Peace. Years later, the Concerned Women of the Philippines established the Doña Aurora Aragon Quezon Peace Awards, choosing the name in honor of this good, quiet, peaceful woman.

The blood stained rosary was brought to Nini, after Philip’s death. Many years later, she wrote down the thoughts that came to her when they gave her the bloody beads:

“We had joined my mother in Baguio for Holy Week, 1949. As we drove down the zigzag, after attending all the Holy Week services, Phil turned to me and said, ‘Nini, if we were to have an accident now, wouldn’t it be the perfect time for us to go?’ I said to him, ‘You may be ready, Phil, but I still have a child to give life to, so I can’t go just yet.’ And not long after this, his life was taken, and mine was spared.”

Her life was spared, but she felt the agony of those three deaths more intensely than anyone else. In that ambush she lost her husband, her mother, and her only sister. The gunmen riddled their bodies with bullets, on that rough mountain road. But miles away, with her one year old baby in her arms, and another baby in her womb, the gunmen left her with a broken heart. The ones she loved went home to God. But she had to carry on.

Another friend of Philip’s, Teodoro M. Locsin, whose wartime diary is also featured in the Philippine Diary Project, wrote about the murder of his friend, in the Philippines Free Press: see One Must Die, May 7, 1949:

I knew Philip slightly before the war. We were together when the Americans entered Manila in February, 1945. We were given a job by Frederic S. Marquardt, chief of the Office of War Information, Southwest Pacific Area, and formerly associate editor of the Free Press. Afterward, Philip would say that he owed his first postwar job to me: I had introduced him to Marquardt.

Philip and I helped put out the first issues of the Free Philippines. We worked together and wrote our stories while shells were going overhead. Philip was never happier; he was in his element. He was at last a newspaperman. He had done some newspaper work before the war, but this was big time. We were covering a city at war. Afterward, we resigned from the OWI, or were fired. Anyway, we went out together.

Meanwhile, we had, with Jose Diokno, the son of Senator Diokno, put out a new paper, the Philippines Press. Diokno was at the desk and more or less kept the paper from going to pieces as it threatened to do every day. I thundered and shrilled; that is, I wrote the editorials. Philip was the objective reporter, the impartial journalist, who gave the paper many a scoop. That was Philip’s particular pride: to give every man, even the devil, his due. While I jumped on a man, Philip would patiently listen to his side…

…As for Philip, he was eager to work, willing to listen, and devoted to the ideals of his craft. He was always smiling—perhaps because he was quite young. He had no enemy in the world—he thought.

After the paper closed up, Philip went to the Manila Post, which suffered a similar fate. Philip went on the radio, as a news commentator. He had a good radio voice; he spoke clearly, forcefully, well. He married the daughter of the late President Manuel L. Quezon, later joined the foreign service. But he never stopped wanting to be again a newspaperman. He would have dropped his work in the government at any time had there been an opening in the press for him.

Philip never spoke ill of Taruc. He saw the movement, of which Taruc was the head, as something he must cover, if given the assignment, and nothing more. Belonging to the landlord class though he did, he did not rave and rant against the Huks.

He had all the advantages, and he had, within the framework of the existing social order, what is called a great future. He was married to a fine girl and all the newspapermen were his friends. They kidded him; they called him Philip Buencamino the Tired, but they all liked him. He wanted so much to be everybody’s friend. he got along with everyone—including myself and Arsenio H. Lacson.

When he returned from Europe to which he had been sent in the foreign service of the Philippines, he was happy, he said, to be home again, and he still wanted to be a newspaperman. His wife was expecting a second child and life was wonderful. Now he is dead, murdered, shot down in cold blood by Taruc’s men.

He was, in the Communist view and in Communist terminology, a representative of feudal landlordism, a bourgeois reactionary, etc. I remember him as a decent young man who tried to be and was a good newspaperman, who used to walk home with me in the afternoon in the early days of Liberation, munching roasted corn and hating no one at all in the world.

A few days earlier, the other friend mentioned by Locsin —Arsenio H. Lacson on May 3, 1949— had also paid tribute to his friend, Philip:

Until now, I can’t quite get over Philip’s tragic death. He was first of all, a very close friend of mine. I saw him married, and was one of the best men at his wedding. I also saw him buried, and it is not a pleasant thing to remember.

Philip was such a nice, clean boy, friendly, warm-hearted and generous, so full of life, and laughter, that I learned to love him. Of course he had his faults, but you take your friends as they are, not as you want them to be. And Philip, for all his faults, was quite a man. In all the years that we kept close together, I never knew him to deliberately do a mean thing.

Because he was by nature easy-going and amiable, he exasperated me at time by failing to take things more seriously and using his considerable talents to point out the many evils with which our government is cursed. Actually, he was not wholly indifferent to them. He could on occasions become quite angry over certain injustices, but he had no capacity for sustained indignation, and it was not in him, to fret and worry over the distraceful and scandalous way this country is being run. Life to him was one swell adventure, to be lived and savored to the full, with very little time left for crusades. The world cannot be changed or saved in a day.

And because he was Philip, he would gaily twit me about being afflicted with a messianic itch. Relax, he would say. Take it easy. Things are not as bad as they look. In time, everything would be alright. Perhaps, he had the right answer. I wouldn’t know. But I shudder to think what would happen if all of us adopted a carely and carefree attitude and paraphrasing archie, Don Marquis’ cockroach reporter, say:

no trick nor kick of fate

can raise me from a yell,

serene I sit and wait

for the Philippines to go to hell.The last time I saw Philip was two days before his death. Linking his arm to mine with a gay laugh, he dragged me to Astoria for a cup of coffee. We joined a boisterous group of newsmen who flung good-natured jibes at Philip when he announced that he was quitting the government foreign service to settle down to a life of a country farmer. Somebody brought up the subject of a certain Malacañan reporter who always made it a point to take a malicious crack at Philip and his influential family connections, and Philip agreed the guy was nasty. It was typical of Philip, however, that when I curtly suggested that he punch the offensive reporter on the nose, he smilingly shook his head saying: “How can I? Every time I get sore, the fellow embraces me and tells me with that silly laugh of his ‘Sport lang, Chief.’ I can’t get mad at him.”

That was Philip. He couldn’t get mad at anyone for long. He liked everybody, even those who, regarding him with envious eyes as a darling Child of Fortune, spoke harshly of him. He was essentially a nice, friendly guy. It was not in him to harm anybody, including those who tried to harm him.

And now he is dead, along with that fine and noble lady who was his mother-in-law, and that vivid, great-hearted, spirited girl who was so much like her great and illustrious father, foully murdered by hunted and persecuted men turned into wild, insensate beasts by grave injustices –men who, in laying ambush for Mr. Quirino and other government officials, brutally and mercilessly struck down innocent victims instead.

Philip Buencamino III had so much to live for: a charming, gracious wife who adored him, a chubby little son who will one day grow up into sturdy manhood with only a dim memory of his father, and another child on the way whom Philip now will never see. Handsome and talented, Philip had his whole future before him. His was a life so full of brilliant promise, and it is a great tragedy that it should have ended soon. He had been a top reporter before he entered the foreign service. With his charm and affability, his personal gifts and family prestige, there was no height he could not have scaled as a diplomat. The pity of it, the futile pitiful waste of it! A nice, clean, promising youngster sacrificed to the warring passions of men who have turned Central Luzon into a charnel house.

Incidentally, a very rare recording exists of Philip during his time as a radio commentator –and a member of the Malacañan Press Corps– you can listen to him being the emcee of sorts, in President Roxas’s first radio press conference.

Readers can access the diary of Victor Buencamino in full, or that of Felipe Buencamino III in full, as well; or, they can go through the entries for April 1942, which include other entries by other diarists who were writing at the same time.

Salvador H. Laurel wrote intermittent diary entries for June 1985, August 1985, September 1985, October 1985, November 1985, and December 1985. They trace the initial vigor, then collapse, of his campaign for the presidency, and the negotiations for his sliding down to be the candidate for the vice-presidency in what emerged as the Aquino-Laurel ticket.

This period is also described in my article, The Road to EDSA. In his article, Triumph of the Will (February 7 1986), Teodoro L. Locsin Jr. described the gathering of political titans that had to be brought into line to support the Cory candidacy:

It is well to remember that the unity she forged was not among dependent and undistinguished clones, like the KBL that Marcos holds in his hand. Doy Laurel, Pepito Laurel, Tañada, Mitra, Pimentel, Adaza, Diokno, Salonga and the handful of others who kept the democratic faith, each in his own fashion, through the long years of martial law, are powerful political leaders in their own right. Each has kept or developed, by sagacity and guts, a wide personal following. Not one thinks himself subordinate to another in what he has contributed to keep alive the democratic faith. As far as Doy is concerned, his compromises had enabled him to kept at least one portion, Batangas, of a misguided country as a territorial example of viable opposition. An example to keep alive the hope that the rest of the country could follow suit and become free in time.

We have forgotten how much strength and hope we derived from the stories of Batangueños guarding the ballot boxes with their lives and Doy’s people keeping, at gunpoint, the Administration’s flying—or was it sailing?—voters from disembarking from the barges in which they had been ferried by the Administration. This is the language Marcos understands, the Laurels seemed to be saying, and we speak it.

We have forgotten the sage advice of Pepito Laurel which stopped the endless discussion about how to welcome Ninoy. Every arrangement was objected to because, someone would remark, Marcos can foil that plan by doing this or that. Pepito Laurel said, “Huwag mo nang problemahin ang problema ni Marcos. His problem is how to stop us from giving Ninoy the reception he deserves. Our problem is to give Ninoy that reception. Too much talk going on here!” that broke the paralysis of the meeting.

This is the caliber of men who were approached with a project of unification that entailed the suspension, perhaps forever, of their own ambitions. Cory would be the presidential candidate, and Doy who had spent substance and energy to create ex nihilo a political organization to challenge the Marcos machine must subordinate himself as her running mate. In exchange, the chieftains would get nothing but more work, worse sacrifices and greater perils. Certainly, no promises.

After two attempts, she emerged, largely through her own persuasive power and in spite of some stupid interference, as the presidential candidate of the Opposition, with Doy as her running mate. She had not yielded an inch of her position that all who would join the campaign must do so for no other consideration than the distinction of being in the forefront of the struggle. This should be enough. She had exercised the power of her disdain.

There is a gap in the diary until it resumes with his entry for February 13-17,1986, in which Doy Laurel mentions discussions with foreign diplomats. Then the diary trails off until the EDSA Revolution begins.

It is interesting to situate his entries with the chronology available. Compare Laurel’s February 22, 1986 entry with the Day One: February 22 chronology, and his February 23, 1986 entry with the Day Two: February 23, chronology, and his February 24, 1986 entry with the Day Three: February 24 chronology, and his February 25, 1986 entry with the Day Four: February 25 chronology. The chronology of the Flight of the Marcoses, contrasts with Laurel’s diary entries for February 26, 1986 and February 27, 1986.

For more, see my Storify story, EDSA: Memories and Meanings, Timelines and Discussions.

The end result would be a bitter parting of ways; see What’s with Doy? October 3, 1987.

Since the other side of the coin involves Ferdinand E. Marcos, see also my Storify story, Remembering Marcos.

The Philippine Diary Project contains a first-hand account by Lydia C. Gutierrez, of the Battle for Manila. In fact her diary covers only ten days: from the start, to the end, of their ordeal.

In his diary, Fr. Juan Labrador OP, wrote of the liberation of the University of Santo Tomas in his entry for February 20, 1945; he talked to survivors and wrote down their stories, for example, see his entry for February 18, 1945, about the massacres in Singalong, De La Salle College, and the German Club; and see the accounts of survivors of the massacre in Intramuros in his diary entry for February 24, 1945; he also toured the city after the fighting and vividly described the ruins of Manila in his diary entry for March 17, 1945. On March 18, 1945 he visited Los Baños, and described the ordeal of prisoners there, and the destruction of Batangas.

From his diary entry, March 20, 1945:

Our new friends repeatedly asked us if we had not feared that such human slaughter would occur; if we did not have any inkling that the Japanese would make such a bloody exit.

Frankly, neither did we foresee or at least suspect such. Had we known it, we would not have submitted to it like lambs. Never did we imagine that a human being, even if he were Japanese, could go down to such a low level of brutality.

For more information, visit The Battle of Manila, in the Presidential Museum and Library site, with an embedded rare color film of the ruins of Manila in 1945. Visit Battle of Manila Online, too.

Mrs. Aurora A. Quezon, Mrs. Jean Faircloth MacArthur, President Manuel L. Quezon, Arthur MacArthur, Maria Aurora Quezon, Corregidor, 1942.

The beginning of World War 2, despite the immediate setback represented by Pearl Harbor, was greeted with optimism and a sense of common cause between Americans and Filipinos. See: Telegram from President Quezon to President Roosevelt, December 9, 1941 and Telegram of President Roosevelt to President Quezon, December 11, 1941

However, in February, 1942, the Commonwealth War Cabinet undertook a great debate on whether to propose the Philippines’ withdrawing from the war, in the hope of neutralizing the country.

The cause of the debate seems to have been the reverses suffered by the Allied War effort: the success of Japanese landings in Lingayen and other places; the withdrawal to Bataan and Corregidor; and the lack of any tangible assistance to the Philippines as Filipino and American troops were besieged in Bataan.

In his diary entry for January 21, 1942, Felipe Buencamino III, in the Intelligence Service in Bataan, visited Corregidor and wrote,

President Manuel Quezon is sick again. He coughed many times while I talked to him. He was in bed when I submitted report of the General regarding political movements in Manila. He did not read it. The President looked pale. Marked change in his countenance since I last had breakfast with his family. The damp air of the tunnel and the poor food in Corregidor were evidently straining his health. He asked me about conditions in Bataan –food, health of boys, intensity of fighting. He was thinking of the hardships being endured by the men in Bataan. He also said he heard reports that some sort of friction exists between Filipinos and American. “How true is that?” The President’s room was just a make-shift affair of six-by-five meters in one of the corridors of the tunnel. He was sharing discomfort of the troops in Corregidor.

The hardships of Filipino soldiers in Bataan –young ROTC cadets had already been turned away when they turned up in recruiting stations in December, 1941, and told to go home (though quite a few would join the retreating USAFFE forces anyway)– was troubling the leadership of the Commonwealth. About a week after the incident above, these concerns were written down for the record: see Letter of President Quezon to Field Marshal MacArthur, January 28, 1942:

At the same time I am going to open my mind and my heart to you without attempting to hide anything. We are before the bar of history and God only knows if this is the last time that my voice will be heard before going to my grave. My loyalty and the loyalty of the Filipino people to America have been proven beyond question. Now we are fighting by her side under your command, despite overwhelming odds. But, it seems to me questionable whether any government has the right to demand loyalty from its citizens beyond its willingness or ability to render actual protection. This war is not of our making. Those that had dictated the policies of the United States could not have failed to see that this is the weakest point in American territory. From the beginning, they should have tried to build up our defenses. As soon as the prospects looked bad to me, I telegraphed President Roosevelt requesting him to include the Philippines in the American defense program. I was given no satisfactory answer. When I tried to do something to accelerate our defense preparations, I was stopped from doing it. Despite all this we never hesitated for a moment in our stand. We decided to fight by your side and we have done the best we could and we are still doing as much as could be expected from us under the circumstances. But how long are we going to be left alone? Has it already been decided in Washington that the Philippine front is of no importance as far as the final result of the war is concerned and that, therefore, no help can be expected here in the immediate future, or at least before our power of resistance is exhausted? If so, I want to know it, because I have my own responsibility to my countrymen whom, as President of the Commonwealth, I have led into a complete war effort. I am greatly concerned as well regarding the soldiers I have called to the colors and who are now manning the firing line. I want to decide in my own mind whether there is justification in allowing all these men to be killed, when for the final outcome of the war the shedding of their blood may be wholly unnecessary. It seems that Washington does not fully realize our situation nor the feelings which the apparent neglect of our safety and welfare have engendered in the hearts of the people here.

MacArthur forwarded this letter to President Roosevelt in Washington, and according to most accounts it triggered unease among American officials. See Telegram from President Roosevelt to President Quezon regarding his letter to Field Marshal MacArthur, January 30, 1942:

I have read with complete understanding your letter to General MacArthur. I realize the depth and sincerity of your sentiments with respect to your inescapable duties to your own people and I assure you that I would be the last to demand of you and them any sacrifice which I considered hopeless in the furtherance of the cause for which we are all striving. I want, however, to state with all possible emphasis that the magnificent resistance of the defenders of Bataan is contributing definitely toward assuring the completeness of our final victory in the Far East.

The Philippine Diary Project provides a glimpse into how this telegram was received. On February 1, 1942, Ramon A. Alcaraz, captain of a Q-Boat, wrote,

Later, I proceeded to the Lateral of the Quezon Family to deliver Maj. Rueda’s pancit molo. Mrs. Quezon was delighted saying it is the favorite soup of her husband. Mrs. Quezon brought me before the Pres. who was with Col. Charles Willoughby G-2. After thanking me for the pancit molo, Quezon resumed his talk with G-2. He seemed upset that no reinforcement was coming. I heard him say that America is giving more priority to England and Europe, reason we have no reinforcement. “Puñeta”, he exclaimed, “how typically American to writhe in anguish over a distant cousin (England) while a daughter (Philippines) is being raped in the backroom”.

The remark quoted above is found in quite a few other books; inactivity and ill-health seemed to be taking its toll on the morale of government officials, while the reality was the Visayas and Mindanao were still unoccupied by the enemy. On February 2, 1942, Gen. Valdes wrote that the idea of evacuating the Commonwealth Government from Corregidor was raised. Another incident seems to have have happened the day after purely by chance, see Evacuation of the Gold Reserves of the Commonwealth, February 3, 1942.

Three days later, however, matters came to a head. It is recorded in the Diary of Gen. Basilio Valdes, February 6, 1942:

The President called a Cabinet Meeting at 9 a.m. He was depressed and talked to us of his impression regarding the war and the situation in Bataan. It was a memorable occasion. The President made remarks that the Vice-President refuted. The discussion became very heated, reaching its climax when the President told the Vice-President that if those were his points of view he could remain behind as President, and that he was not ready to change his opinion. I came to the Presidents defense and made a criticism of the way Washington had pushed us into this conflict and then abandoning us to our own fate. Colonel Roxas dissented from my statement and left the room, apparently disgusted. He was not in accord with the President’s plans. The discussion the became more calm and at the end the President had convinced the Vice-President and the Chief Justice that his attitude was correct. A telegram for President Roosevelt was to be prepared. In the afternoon we were again called for a meeting. We were advised that the President had discussed his plan with General MacArthur and had received his approval.

The great debate among the officials continued the next day, as recounted in the Diary of General Basilio Valdes, February 7, 1942:

9 a.m. Another meeting of the Cabinet. The telegram, prepared in draft, was re-read and corrected and shown to the President for final approval. He then passed it to General MacArthur for transmittal to President Roosevelt. The telegram will someday become a historical document of tremendous importance. I hope it will be well received in Washington. As a result of this work and worry the President has developed a fever.

The end results was a telegram sent to Washington. See Telegram of President Quezon to President Roosevelt, February 8, 1942:

The situation of my country has become so desperate that I feel that positive action is demanded. Militarily it is evident that no help will reach us from the United States in time either to rescue the beleaguered garrison now fighting so gallantly or to prevent the complete overrunning of the entire Philippine Archipelago. My people entered the war with the confidence that the United States would bring such assistance to us as would make it possible to sustain the conflict with some chance of success. All our soldiers in the field were animated by the belief that help would be forthcoming. This help has not and evidently will not be realized. Our people have suffered death, misery, devastation. After 2 months of war not the slightest assistance has been forthcoming from the United States. Aid and succour have been dispatched to other warring nations such as England, Ireland, Australia, the N. E. I. and perhaps others, but not only has nothing come here, but apparently no effort has been made to bring anything here. The American Fleet and the British Fleet, the two most powerful navies in the world, have apparently adopted an attitude which precludes any effort to reach these islands with assistance. As a result, while enjoying security itself, the United States has in effect condemned the sixteen millions of Filipinos to practical destruction in order to effect a certain delay. You have promised redemption, but what we need is immediate assistance and protection.We are concerned with what is to transpire during the next few months and years as well as with our ultimate destiny. There is not the slightest doubt in our minds that victory will rest with the United States, but the question before us now is : Shall we further sacrifice our country and our people in a hopeless fight? I voice the unanimous opinion of my War Cabinet and I am sure the unanimous opinion of all Filipinos that under the circumstances we should take steps to preserve the Philippines and the Filipinos from further destruction.

Again, by most accounts, there was great alarm in Washington over the implications of the telegram, and after consultations with other officials, a response was sent. See Telegram of President Roosevelt to President Quezon, February 9, 1942:

By the terms of our pledge to the Philippines implicit in our 40 years of conduct towards your people and expressly recognized in the terms of the McDuffie—Tydings Act, we have undertaken to protect you to the uttermost of our power until the time of your ultimate independence had arrived. Our soldiers in the Philippines are now engaged in fulfilling that purpose. The honor of the United States is pledged to its fulfillment. We propose that it be carried out regardless of its cost. Those Americans who are fighting now will continue to fight until the bitter end. So long as the flag of the United States flies on Filipino soil as a pledge of our duty to your people, it will be defended by our own men to the death. Whatever happens to the present American garrison we shall not relax our eiforts until the forces which we are now marshaling outside the Philippine Islands return to the Philippines and drive the last remnant of the invaders from your soil.

Still, seizing the moment, the Commonwealth officials pursued their proposal; see Telegram of President Quezon to President Roosevelt, February 10, 1942:

I propose the following program of action: That the Government of the United States and the Imperial Government of Japan recognize the independence of the Philippines; that within a reasonable period of time both armies, American and Japanese, be withdrawn, previous arrangements having been negotiated with the Philippine government; that neither nation maintain bases in the Philippines; that the Philippine Army be at once demobilized, the remaining force to be a Constabulary of moderate size; that at once upon the granting of freedom that trade agreement with other countries become solely a matter to be settled by the Philippines and the nation concerned; that American and Japanese non combatants who so desire be evacuated with their own armies under reciprocal and appropriate stipulations. It is my earnest hope that, moved by the highest considerations of justice and humanity, the two great powers which now exercise control over the Philippines will give their approval in general principle to my proposal. If this is done I further propose, in order to accomplish the details thereof, that an Armistice be declared in the Philippines and that I proceed to Manila at once for necessary consultations with the two governments concerned.

But it was not to be; the next day the reply from Washington came. Telegram of President Roosevelt to President Quezon, February 11, 1942:

Your message of February tenth evidently crossed mine to you of February ninth. Under our constitutional authority the President of the United States is not empowered to cede or alienate any territory to another nation.

In the Philippine Diary Project, the despondent response to this telegram is recorded. See Diary of Gen. Basilio Valdes, February 11, 1942:

Had a Cabinet Meeting. The reply of President Roosevelt to President Quezon’s radio was received. No, was the reply. It also allowed General MacArthur to surrender Philippine Islands if necessary. General MacArthur said he could not do it. The President said that he would resign in favor of Osmeña. There was no use to dissuade him then. We agreed to work slowly to convince him that this step would not be appropriate.

By the next day, cooler heads had prevailed; the response was then sent to Washington. See Telegram of President Quezon to President Roosevelt, February 12, 1942:

I wish to thank you for your prompt answer to the proposal which I submitted to you with the unanimous approval of my war cabinet. We fully appreciate the reasons upon which your decision is based and we are abiding by it.

From then on, the question became where it would be best to continue the operations of the government; and plans were resumed to move the government to unoccupied territory in the Visayas. The sense of an unfolding, unstoppable, tragedy seems to have overcome many involved. From the Diary of Gen. Basilio Valdes, February 12, 1942:

The President had a long conference with General MacArthur. Afterwards he sent for me. He asked me: “If I should decide to leave Corregidor what do you want to do?” “I want to remain with my troops at the front that is my duty” I replied. He stretched his hand and shook my hand “That is a manly decision; I am proud of you” he added and I could see tear in his eyes. “Call General MacArthur” he ordered “I want to inform him of your decision.” I called General MacArthur. While they conferred, I went to USAFFE Headquarters tunnel to confer with General Sutherland. When General MacArthur returned he stretched his hand and shook hands with me and said “I am proud of you Basilio, that is a soldier’s decision.” When I returned to the room of the President, he was with Mrs. Quezon. She stood up and kissed me, and then cried. The affection shown to me by the President & Mrs. Quezon touched me deeply. Then he sent for Manolo Nieto and in our presence, the President told Mrs. Quezon with reference to Manolo, “I am deciding it; I am not leaving it to him. I need him. He has been with me in my most critical moments. When I needed someone to accompany my family to the States, I asked him to do it. When I had to be operated I took him with me; now that need him more then ever, I am a sick man. I made him an officer to make him my aide. He is not like Basilio, a military man by career. Basilio is different, I forced him to accept the position he now had; his duty is with his troops”. Then he asked for Whisky and Gin and asked us to drink. Colonel Roxas and Lieutenant Clemente came in. We drank to his health. He made a toast: “To the Filipino Soldier the pride of our country”, and he could not continue as he began to cry.

On February 15, 1942, Singapore fell to the Japanese. Five days later, the Commonwealth government departed Corregidor to undertake an odyssey that would take it from the Visayas to Mindanao and eventually, Australia and the United States. See Escape from Corregidor by Manuel L. Quezon Jr.

Though never publicized (for obvious reasons) by the Americans, the proposal to neutralize the Philippines was viewed important enough by Filipino leaders to merit the effort to ensure the proposal would be kept for the record.

From the Diary of Gen. Basilio Valdes, April 11, 1942:

The President called a Cabinet meeting at 3 p.m. Present were the Vice-President, Lieutenant Colonel Soriano, Colonel Nieto and myself. He discussed extensively with us the war situation. The various radiograms he sent to President Roosevelt and those he received were read. All together constitute a valuable document of the stand the President and his War Cabinet has taken during the early part of the war. The meeting was adjourned at 6 p.m.

In the Philippine Diary Project, Francis Burton Harrison’s diary entry for June 22, 1942 has a candid account by Quezon of this whole period and his frame of mind during that period:

Exchange of cables between Quezon in Corregidor and Roosevelt: Quezon advised him that he was in grave doubts as to whether he should encourage his people to further resistance since he was satisfied that the United States could not relieve them; that he did not see why a nation which could not protect them should expect further demonstrations of loyalty from them. Roosevelt in reply, said he understood Quezon’s feelings and expressed his regret that he could not do much at the moment. He said: “go ahead and join them if you feel you must.” This scared MacArthur. Quezon says: “If he had refused, I would have gone back to Manila.” Roosevelt also promised to retake the Philippines and give them their independence and protect it. This was more than the Filipinos had ever had offered them before: a pledge that all the resources and man power of United States were back of this promise of protected independence. So Quezon replied: “I abide by your decision.”

I asked him why he supposed Roosevelt had refused the joint recommendation of himself and MacArthur. He replied that he did not know the President’s reasons. Osmeña and Roxas had said at the time that he would reject it. Roosevelt was not moved by imperialism nor by vested interests, nor by anything of that sort. Probably he was actuated by unwillingness to recognize anything Japan had done by force (vide Manchuria). Quezon thinks that in Washington only the Chief of Staff (General Marshall) who received the message from MacArthur in private code, and Roosevelt himself, knew about this request for immediate independence.

When Quezon finally got to the White House, Roosevelt was chiefly concerned about Quezon’s health. Roosevelt never made any reference to their exchange of cables.

Quezon added that, so far as he was aware, the Japanese had never made a direct offer to the United States Government to guarantee the neutrality of the Philippines, but many times they made such an offer to him personally.

“It was not that I apprehended personally ill treatment from the Japanese” said Quezon; “What made me stand was because I had raised the Philippine Army–a citizen army–I had mobilized them in this war. The question for me was whether having called them, I should go with this army, or stay behind in Manila with my people. I was between the Devil and the deep sea. So I decided that I should go where the army did. That was my hardest decision–my greatest moral torture. I proposed by cable to President Roosevelt that the United States Government should advise the Japanese that they had granted independence to the Philippines. This should have been done before the invasion and immediately after the first Japanese attack by air. The Japanese had repeatedly offered to guarantee the neutrality of an independent Philippines. This was what they thought should be done.” Quezon is going to propose the passage by Congress of a Joint Resolution, as they did in the case of Cuba, that “the Philippines are and of right out to be independent” and that “the United States would use their armed forces to protect them.”

When asked by Shuster to try to describe his own frame of mind when he was told at 5:30 a.m. Dec. 8 of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Quezon said he had never believed that the Japanese would dare to do it; but since they had done so, it was at once evident that they were infinitely more powerful than had been supposed– therefore he immediately perceived that the Philippines were probably doomed.

A postscript would come in the form a radio broadcast beamed to occupied Philippines. See the Inaugural Address of President Manuel L. Quezon, November 15, 1943:

I realize how sometimes you must have felt that you were being abandoned. But once again I want to assure you that the Government and people of the United States have never forgotten their obligations to you. General MacArthur has been constantly asking for more planes, supplies and materials in order that he can carry out his one dream, which is to oust the Japanese from our shores. That not more has been done so far is due to the fact that it was simply a matter of inability to do more up to the present time. The situation has now changed. I have it on good authority that General MacArthur will soon have the men and material he needs for the reconquest of our homeland. I have felt your sufferings so deeply and have constantly shared them with you that I have been a sick man since I arrived in Washington, and for the last five months I have been actually unable to leave my bed. But sick as I was, I have not for a moment failed to do my duty. As a matter of fact the conference which resulted in the message of President Roosevelt was held practically in my bedroom. Nobody knows and feels as intensely as I do your sufferings and your sacrifices, how fiercely the flame of hate and anger against the invader burns in your hearts, how bravely you have accepted the bitter fact of Japanese occupation. I know your hearts are full of sorrow, but I also know your faith is whole. I ask you to keep that faith unimpaired. Freedom is worth all our trials, tears and bloodshed. We are suffering today for our future generations that they may be spared the anguish and the agony of a repetition of what we are now undergoing. We are also building for them from the ruins of today and thus guarantee their economic security. For the freedom, peace, and well-being of our generations yet unborn, we are now paying the price. To our armed forces, who are fighting in the hills, mountains and jungles of the Philippines, my tribute of admiration for your courage and heroism. You are writing with your sacrifices another chapter in the history of the Philippines that, like the epic of Bataan, will live forever in the hearts of lovers of freedom everywhere.

Victor Buencamino:

Lydia C. Gutierrez:

Francis Burton Harrison:

February 29, 1936: entry completed

Juan Labrador:

Ferdinand E. Marcos

Basilio J. Valdes:

Commonwealth War Cabinet-in-exile: (l. to r. ) Defense Secretary Gen. Basilio J. Valdes, Resident Commissioner Joaquin Elizalde, President Manuel L. Quezon, Vice President Sergio Osmeña, Finance Secretary Andres Soriano, Auditor-General Jaime Hernandez. Washington, D.C, May, 1942.

The February 3, 1942 diary entry of Gen. Basilio J. Valdes mentions a “secret and delicate mission.” This was the transfer of the gold reserves of the Philippine Government from vaults in Corregidor to a U.S. submarine, which brought the reserves to the United States.

Read the story of the transportation and accounting of those gold reserves.

Victor Buencamino:

Francis Burton Harrison:

January 30-31 & February 1-2, 1936

Juan Labrador:

Ferdinand E. Marcos:

Basilio J. Valdes:

To mark the anniversary of the Battle of Manila, starting tomorrow, we will be publishing the Liberation Diary of Lydia C. Gutierrez, which was originally published in the Sunday Times Magazine in 1967.

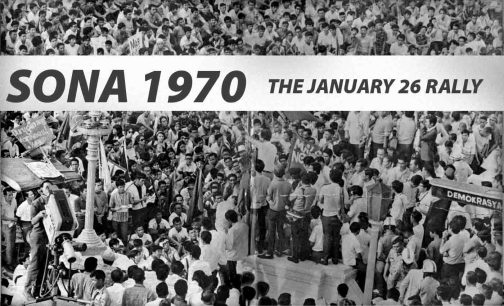

Prior to the scrapping of the 1935 Constitution, presidents would deliver their State of the Nation Address in January, at the Legislative Building in Manila.

On January 26, 1970, President Marcos, who had been inaugurated for an unprecedented full second term less than a month earlier, on December 30, 1969 (see Pete Lacaba’s satirical account, Second Mandate: January 10, 1970), was set to deliver his fifth message to the nation.

The classic account of the start of what has come to be known as the First Quarter Storm is Pete Lacaba’s The January 26 Confrontation: A Highly Personal Account, February 7, 1970 followed by his And the January 30 Insurrection, February 7, 1970. From another point of view, there is Kerima Polotan’s The Long Week, February 7, 1970. Followed by Nap Rama’s Have rock, will demonstrate, March 7, 1970.

And there, is of course, the view of Ferdinand E. Marcos himself.

January 23, 1970 and January 24, 1970 were mainly about keeping an eye out on coup plots and the opposition, as well as reshuffling the top brass of the armed forces and picking a new Secretary of National Defense.

January 25, 1970 was about expressing his ire over the behavior of student leaders.

On January 26, 1970 Marcos wrote,

After the State of the Nation address, which was perhaps my best so far, and we were going down the front stairs, the bottles, placard handles, stones and other missiles started dropping all around us on the driveway to the tune of a “Marcos, Puppet” chant.

Marcos then noted,

Some advisors are quietly recommending sterner measures against the Kabataang Makabayan. We must get the emergency plan polished up.

January 27, 1970 and January 28, 1970 were spent housekeeping –talking to police generals– and warning the U.S. Embassy they had better not get involved. Marcos began to further flesh out the rationale for his forthcoming emergency rule:

If we do not prepare measures of counter-action, they will not only succeed in assassinating me but in taking over the government. So we must perfect our emergency plan.

I have several options. One of them is to abort the subversive plan now by the sudden arrest of the plotters. But this would not be accepted by the people. Nor could we get the Huks, their legal cadres and support. Nor the MIM and other subversive [or front] organizations, nor those underground. We could allow the situation to develop naturally then after massive terrorism, wanton killings and an attempt at my assassination and a coup d’etat, then declare martial law or suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus – and arrest all including the legal cadres. Right now I am inclined towards the latter.

On January 29, 1970 Marcos rather angrily recounted receiving a delegation of faculty from his alma mater, the University of the Philippines; and reports in his diary that a very big student protest is due the next day.

The next day would prove to be even more explosive than the day of Marcos’ State of the Nation Address: the attack on Malacañan Palace by student protesters. Marcos writes about it in his January 30, 1970 diary entry:

…the Metrocom under Col. Ordoñez and Aguilar after reinforcement by one company of the PC under Gen. Raval arrived have pushed up to Mendiola near San Beda where the MPD were held in reserve. I hear shooting and I am told that the MPD have been firing in the air.

The rioters have been able to breach Gate 4 and I had difficulty to stop the guards from shooting the rioters down. Specially as when Gate 3 was threatened also. I received a call from Maj. Ramos for permission to fire and my answer was “Permission granted to fire your water hoses.”

For an overview of the events of that day, see Pete Lacaba’s And the January 30 Insurrection, February 7, 1970. This was another in what would turn out to be historic reportage on historic times; as counterpoint (from a point of view far from enamored of the students) see Kerima Polotan’s account mentioned above.

The next day, January 31, 1972, Marcos further fleshed out his version of the student attack on the Palace, and begins enumerating more people to keep an eye on –politicians, media people; he also mentions the need to suspend the Writ of Habeas Corpus –eventually.

For an overview of the First Quarter Storm, see also Manuel L. Quezon III’s The Defiant Era, January 30, 2010.

Victor Buencamino:

Francis Burton Harrison:

Juan Labrador:

Ferdinand E. Marcos:

Other updates:

We will be adding two new diaries to the Philippine Diary Project:

The Clinical Record of President Manuel L. Quezon, the journal kept by his doctors and nurses from April 18-August 1, 1944.

The Liberation Diary of Lydia C. Gutierrez, covering one week of events during the Battle of Manila in February, 1945.

Earlier, we started adding entries from the Diary of Victor Buencamino (the first Filipino veterinarian), who was the father of another diarist featured in the project, Felipe Buencamino III. While Felipe Buencamino III was in Bataan, his father was serving as manager of NARIC, precursor of today’s National Food Authority.

Victor Buencamino:

January 2, 1942: entry completed

Francis Burton Harrison:

Juan Labrador, OP:

Ferdinand E. Marcos:

Basilio J. Valdes:

January 19, 1942: corrected some names

Antonio de las Alas:

June 26, 1945: completed entry

Francis Burton Harrison:

February 11, 1936: completed entry

Ferdinand E. Marcos:

Victor Buencamino:

Francis Burton Harrison:

August 11, 1936: completed entry

Salvador H. Laurel:

Ferdinand E. Marcos:

Rafael Palma:

Photo above: recently offered for sale on eBay, a Baltimore Sun wirephoto of wounded soldiers aboard the S.S. Mactan.

Late at night, on December 31, 1941, an old ship prepared to weigh anchor to escape Manila. Its destination was Sydney, Australia. On board, were 224 wounded USAFFE soldiers (134 of them Americans and 90 of whom were Filipinos); 67 crew members, all Filipino, and 25 medical and Red Cross personnel, all Filipino except for one American nurse, and some others.

The ship was the S.S. Mactan. Its journey represents one of the great escapes of World War 2.

In the book At His Side: The Story of the American Red Cross Overseas in World War 2, by George Korson, chronicles the story of the S.S. Mactan.

Page 22 of the book contains this scene:

On the morning of December 24, some twenty Red Cross volunteer women were in the official residence of Francis B. Sayre, High Commissioner to the Philippines, packing Christmas gifts for soldiers and sailors in hospitals in and around Manila. Mrs. Sayre was in charge of the group.

Suddenly, at eleven o’clock, Mrs. Sayre looked up from her task at the tables to see her husband standing in the patio doorway beck- oning to her. She slipped quietly out of the room and stood in the patio. “I have an urgent message from General MacArthur,” said Mr. Sayre in a low voice. “The city may fall, and we must be ready to leave for Corregidor at one-thirty!”

Mrs. Sayre was stunned. “But we must finish these bags. They’re the only Christmas our boys will have.”

“Pack as quickly as you can,” he said and left hurriedly. Mrs. Sayre went back to the tables. The women worked quickly, and in silence, to complete their task before the daily noon Japanese air raid over Manila.

The treasure bags, as they were called, made hundreds of American and Filipino soldiers and sailors happier in their hospital wards that dark Christmas Day. Irving Williams helped Gray Ladies make the distribution in the Sternberg General Hospital. The work was under the direction of Miss Catherine L. Nau, of Pittsburgh assistant field director at the hospital, who later was to distinguish herself for her work among the troops on Bataan and Corregidor, before the Japanese interned her.

Of the gift distribution at Sternberg General Hospital, Irving Williams said, “I shall never forget the boys’ beaming faces and delighted eyes as we went from ward to ward. The simple comfort articles meant so much to these boys, who had lost all of their possessions on the field of battle.”

The Philippine Diary Project contains General Basilio J. Valdes’ diary entry for December 24, 1941, giving the Filipino side of that day’s hectic events.

The Red Cross book continues with Gen. Valdes returning to Manila to contact the Red Cross:

Not until three days later December 28 did Williams know that these same boys would be entrusted to his care on one of the most hazardous missions of the war. Major General Basilio Valdes, then commanding general of the Filipino Army, came straight from MacArthur’s headquarters on Corregidor with the urgent request that the American Red Cross undertake to transport all serious casualties from the Sternberg General Hospital to Australia. President Manuel Quezon of the Philippine Commonwealth helped the Red Cross locate the Mactan.

The Commonwealth Government had, of course, by this time, withdrawn to Corregidor, and Manila had been declared an Open City. Sending Gen. Valdes to Manila was therefore rather risky.

The Philippine Diary Project contains Gen. Valdes’ entries about this mission, which began on December 28, 1941:

We left Corregidor on a Q Boat. It took us 45 minutes to negotiate the distance. The picture of Manila Bay with all the ships either sunk or in flames was one of horror and desolation. We landed at the Army and Navy Club.

I rushed immediately to Red Cross Headquarters. I informed Mr. Forster, Manager Philippine Red Cross, and Mr. Wolff, Chairman of the Executive Board of my mission. I then called the Collector of Customs Mr. de Leon and I asked him what ships were still available for my purpose. He offered the government cutter Apo. I accepted. He told me that it was hiding somewhere in Bataan and that he expected to hear from the Captain at 6 p.m.

From his house, I rushed to Sternberg General Hospital where I conferred with Colonel Carroll regarding my plans. Then I returned to the Red Cross Headquarters and arranged for 100 painters and sufficient paint to change its present color to white, with a huge Red Cross in the center of the sides and on the funnel.

At 3 p.m. I again called Collector de Leon and inquired if he would try to contact the Apo. He assured me that he would endeavor to contact the Captain (Panopio). At 11 p.m. Mr. De Leon phoned me that he had not yet received any reply to his radio call. I could not sleep. I was worried.

There’s an extensive chronicle in his diary entries for December 29, 1941:

At 6:30 a.m. I called up Mr. Jose (Peping) Fernandez one of the managers of Compania Maritima and told him that I had to see him with an important problem. I rushed to his house. He realized my predicament. “I can offer you ships, but they are not here,” he said. After studying my needs from all angles we decided that the best thing to do would be to ask the U.S. Army to release the SS Mactan.

We contacted Colonel George, in charge of water transportation, and asked him to meet us at USAFFE Headquarters so that we could discuss the matter with General Marshall. We met at 8 a.m. and it was decided that the U.S. Army would release the Mactan to me to convert it into a hospital ship. I was told the SS Mactan, was in Corregidor and it would not be in Manila until after dark. I rushed to the Red Cross Headquarters and asked Mr. Forster to have the painters in readiness to start the painting without delay, as soon as the ship docked at Pier N-1.

Last night Mr. Forster sent a telegram to the American Red Cross in Washington informing them of our plan.

At 11 a.m. Collector de Leon phoned me that the Apo was sailing for Manila that evening. I thanked him and informed him that it was too late.

At 5 p.m. Mr. Wolff phoned me that they have received an important radiogram from the Secretary of State, Hull, and that my presence in the Red Cross was urgent to discuss the contents of this radiogram. I rushed there. Mr. Wolff, Mr. Forster, Judge Dewitt and Dr. Buss of the High Commissioner’s Office were already busy studying the contents of Mr. Hull’s radiogram. It was specified in it that the sending out of Red Cross hospital Ship was approved; that the Japanese government had been advised of its sailing through the Swiss Ambassador and that it was necessary that we radio rush the name of the ship and the route that would be followed. Moreover, we were told to comply strictly with the articles of the Hague convention of 1907. These articles define what is meant by Red Cross Hospital Ship, how it must be painted and what personnel it must carry. It clearly specifies that no civilian can be on the boat.

I left Red Cross Headquarters at 6:30 p.m. No news of the SS Mactan had been received. At 9 p.m. I called Dr. Canuto of the Red Cross, and I was advised that the ship had not yet arrived.

At 11 p.m. I went to Pier N-1 to inquire. No one could give me any information about the Mactan…

And December 30, 1941:

At 5 a.m. Mr. Williams of the Red Cross phoned me that the ship had arrived but that he was not willing to put the painters on because there was still some cargo of rifles and ammunition left. He informed me that the Captain (Tamayo) and the Chief Officers were in his office. I asked him to hold them. I dressed hurriedly and rushed to the Red Cross Headquarters. They repeated the information given to Mr. Williams. Believing that this cargo belonged to the U.S. Army I asked them to come with me to the USAFFE Headquarters. I had to awake General Marshall. Pressing our inquiry we found out that this cargo consisted only of 3 or 4 boxes of rifles (Enfield) and 2 boxes of 30 caliber ammunition belonging to Philippine Army. It had been left as they were forced to leave Corregidor before everything had been unloaded. We explained to them that there was no danger and with my assurance that these boxes would be unloaded early in the morning, they returned to the ship, took on the painters and left for Malabon for the painting job.

From the USAFFE Headquarters, I rushed to the house of Colonel Miguel Aguilar, Chief of Finance. I found him in bed. He got up, and I asked him to see that the remaining cargo there be removed without delay. He assured me that he would contact the Chief of Quartermaster Service and direct him accordingly. My order was complied with during the course of the day.

At 9 a.m. I contacted Mr. Forster. He informed me that the painters were on the job and that in accordance with my instructions, two launches were tied close to the ship to transport the painters to the river of Malabon in case of a raid. I then went to Colonel Aguilar’s office at the Far Eastern University to discuss with him some matters regarding finance of the Army. From there I went to Malacañan to see Sec. Vargas, and from there to the office of the Sec. of National Defense, to inquire for correspondence for me.

At noon, I called Mr. Jose (Peping) Fernandez to inquire where the ship was. He asked me to have luncheon with him and to go afterwards to Malabon. After lunch we went by car to Malabon. I saw the ship being painted white. It already had a large Red Cross on the sides and on the funnel.

I returned to the Red Cross Headquarters to ascertain if all plans had been properly carried out. Mr. Forster was worried as he did not know whether the provisions and food supplies carried by his personnel would be sufficient. I then contacted Colonel Ward by phone, and later Colonel Carroll. Both assured me that there would be enough food and medical supplies for the trip.

With that assurance, and the promise of Mr. Forster that his doctors and nurses were all ready to go and of Colonel Carroll that as soon as the boat docked at Pier 1, he would begin to load his equipment, beds, etc. and transport his patients, I felt that my mission had been successfully accomplished.

Here, the Red Cross book continues the story on page 16:

Late in the afternoon of December 31, 1941, Army ambulances came clanging down Manila’s Pier 1 and halted alongside the American Red Cross hospital ship Mactan moored there.

They were followed by others, and for three hours an unending line of stretchers bearing seriously wounded American and Filipino soldiers streamed up the Mactan’s gangplank. Men with bandaged heads, with legs in casts, with arms in slings, and with hidden shrapnel wounds were borne aloft by Filipino doctors, nurses, and crew.

Their faces pallid and eyes expressionless, they had no idea where they were being taken. They did not seem to care, except that the large red crosses on the ship’s sides were a reassuring sign that they were in friendly hands.

There were 224 officers and enlisted men in the group of wounded young boys of the new Philippine Army, youthful American airmen, grizzled veterans of the Philippine Scouts (an arm of the United States Army), and gray-haired American soldiers with many years’ service in the Far East. All had been wounded fighting the Japanese invaders during the bloody weeks preceding the historic stand on Bataan.

These casualties had been left behind in the Sternberg General Hospital when General Douglas MacArthur withdrew his forces to Bataan. Anxious, however, to save them from the rapidly advancing Japanese armies, he had requested the American Red Cross to transport them to Darwin, Australia, in a ship chartered, controlled, staffed, and fully equipped by the Red Cross. The only military personnel aboard, apart from the patients, would be an Army surgeon, Colonel Percy J. Carroll, of St. Louis, Missouri, and an Army nurse, Lieutenant Floramund Ann Fellmeth, of Chicago.

Aboard the Mactan, berthed at Manila’s only pier to survive constant Japanese air attacks, Irving Williams, of Patchogue, Long Island, lanky Red Cross field director, observed the three-hour procession of wounded up the gangplank. From now on until the ship reached Australia an estimated ten-day passage if things went well responsibility for them was in his hands.

The book on page 16 continues by explaining how the Mactan ended up the chosen ship for this mission:

Only forty-eight hours had elapsed since the Mactan had been brought from Corregidor where she was unloading military stores for the United States Army. A 2,000-ton, decrepit old Philippine inter-island steamer, she was the only ship available at the time when everything in Manila Bay had been sunk or scuttled or had scampered off to sea.

Working under threat of Manila’s imminent occupation by Japanese troops, Williams and his Red Cross associates, and the crews under them, performed a miracle of speed in outfitting the Mactan as a hospital ship. Simultaneously, steps were taken to fulfill the obligations of international law governing hospital ships: The Mactan was painted white with a red band around the vessel and large red crosses on her sides and top decks; a charter agreement was made between the American Red Cross and the ship’s owners; the ship was commissioned in the name of the President of the United States; in accordance with cabled instructions from Chairman Norman H. Davis in the name of the American Red Cross, the Japanese Government was apprized of the ship’s description and course; all contraband was dumped overboard; and the Swiss Consul, after a diligent inspection as the representative of United States interests, gave his official blessings.

The Mactan, lacking charts to navigate the mine-infested waters of Manila Bay, set steam late in the evening of December 31, 1941. The Philippine Diary Project has Gen. Basilio J. Valdes solving the problem of the charts (involving the charts of the presidential yacht, Casiana, recently sunk off Corregidor), in his entry for December 31, 1941:

At 5 p.m. while I was at Cottage 605, the telephone rang. It was a long distance from Manila. I rushed to answer. It was my aide Lieutenant Gonzalez informing that the ship would be ready to sail, but the Captain refused to leave unless he had the charts for trip, and same could not be had in Manila. I told Lieutenant Gonzalez to hold the line and I asked Colonel Huff who was at General MacArthur’s Quarters next door, and he told me that the charts of the Casiana could be given. I informed Lieutenant Gonzalez. Half an hour later Lieutenant Gonzales again called me and told me that the boat would leave at 6:30 p.m.

I was tired. After dinner I retired. At 10:30 p.m. a U.S. Army Colonel woke me up to inform me that the ship was still in Pier N-1 and that the Captain refused to sail unless he had the charts. We contacted USAFFE Headquarters. We were informed that the Don Esteban was within the breakwater. We gave instructions that the charts of the Don Esteban be given to the Captain of the SS Mactan and that those of the Casiana would be given to the SS Don Esteban.

I then called Collector of Customs Mr. de Leon, and asked him to see that the ship sails even if he had to put soldiers on board and place the Captain under arrest.

At 11:40 p.m. we were advised by phone that the SS Mactan, the hospital ship had left the Pier at 11:30 p.m. We all gave a sigh of relief.

The Red Cross book describes the ship’s departure as follows om p. 19:

Off the breakwater, the Mactan dropped anchor to await the Don Esteban.

As the hours passed, a little group joined Julian C. Tamayo, the Mactan’s skipper, on the bridge for a last look at Manila’s skyline. Besides Williams, there were Father Shanahan, Colonel Carroll, and Chief Nurse Ann Fellmeth.

Having been declared an open city, Manila once again was ablaze. The incandescent lights, however, were dimmed by the curtains of bright flame hanging over the city. The Army was dynamiting gasoline storage tanks at its base in Pandacan and its installations on Engineer Island to prevent their use by the enemy. The docks were burning, and over smoldering Cavite Navy Yard, devastated by heavy Japanese air attacks, intermittent flashes of fire reddened the sky.

As if by design, promptly at midnight the last of the Pandacen gasoline tanks blew up with a terrific explosion, throwing up masses of flame which seemed to envelop the whole city. A new year was ushered in, but the little group on the Mactan’s bridge was in no mood for celebration.

The charts brought by the Don Estebarfs master were not the ones Captain Tamayo had asked for. They were too general.

“Do you think you can sail without detailed charts?” askedWilliams.

“I think so,” replied the swarthy, pug-nosed little skipper with characteristic confidence.Once again, the Mactan weighed anchor. The moon was high in the sky as the ship approached Corregidor for a last-minute rendezvous with a United States naval vessel. From the shadow of The Rock sped a corvette, a gray wraith floodlighted by the moon, to lead the Mactan through the maze of mine fields. The corvette led the lumbering Mactan a merry chase; highly maneuverable, the former made the various turns at sharp angles, while the latter would reach the apex of a triangle and extend beyond it before making a turn.

A 26 year old American nurse, Floramund Fellmeth Difford, who ended up on board after being given a daring assignment, has her own version of events:

While the other nurses stationed in Manila were evacuated to Bataan and Corregidor, Difford was chosen for a special assignment because of her surgical nurse experience. A plan was devised to evacuate as many of the hospitalized soldiers as possible to Australia aboard an inter-island coconut husk steamer called the Mactan, under the auspices of the International Red Cross. It would be the largest single humanitarian evacuation of military personnel to date. And it was a suicide mission.

Col. Percy J. Carroll, the commanding officer of the Manila Hospital Center, told Difford the secret assignment was voluntary and risky. There was no guarantee the ship, which was barely seaworthy, would make it to its destination, but for the wounded, staying in Manila meant certain death. “It never really entered my mind to refuse, as we were accustomed to following orders,” Difford related in her book.

While the Japanese were on the outskirts of Manila, Difford awaited word to board the Mactan. She carried with her a note that explained that she was a noncombatant, but with the Japanese closing in, she prepared herself to become a prisoner. On Dec. 31, 1941, the order finally came. The Mactan, newly painted white with red crosses on its sides and decks so planes would recognize it as a “mercy ship,” was loaded with 224 wounded soldiers (134 Americans and 90 Filipinos); 67 crew members, all Filipino; and 25 medical and Red Cross personnel, all Filipino except Difford, who was the chief nurse, Col. Carroll, and a Catholic priest from Connecticut, the Rev. Thomas Shanahan, the ship’s chaplain.

Although the Red Cross was given clearance for the ship to leave by a Japanese commander, this was the first hospital ship to transport wounded soldiers in a war that the United States had just entered. There was great concern that the ship would be attacked by air or torpedo. Those aboard the ship rang in New Year’s Day 1942 to the sight of Manila in flames as the Americans blew up gasoline storage tanks to keep the supplies out of enemy hands.

The journey was fraught with peril. The ship had to zigzag through a maze of mines just to leave Manila Bay, following a Navy ship for guidance, and had a close call when it made a wrong turn in the darkness. The ship was infested with cockroaches, red ants, and copra beetles. Violent storms tossed the ship and drenched the patients on their cots on the decks, sheltered only by canvas. There was a fire in the engine room, and for a time those aboard prepared to abandon ship. Two wounded soldiers died from their injuries during the crossing, and a depressed Filipino soldier committed suicide by jumping overboard.

On Jan. 27, 1942, the Mactan arrived in Sydney Harbor to much fanfare, especially after newspapers had falsely reported that the ship had been attacked multiple times. Despite the primitive conditions aboard the vessel, the wounded soldiers arrived in very good condition and were quickly taken to a hospital on land. The Mactan’s voyage made headlines in the United States. Difford was cited for bravery by Gen. Douglas MacArthur and was awarded the Legion of Merit in 1942, among other awards. She and other military nurses were belatedly awarded the Bronze Star Medal for their service in 1993.

On board the ship, Major William A. Fairfield, kept a diary –he called it a “log”– from January 1, 1942, when the S.S. Mactan left Manila, to January 27, 1942, when they entered Sydney Harbor. You can read his diary and his recollections of the opening weeks of the war in the Philippines.

At the end of the voyage, the soldiers who’d been saved, all signed the document:

S. S. Mactan, Red Cross Hospital Ship

At Sea, January 12, 1942National Headquarters

American Red Cross

Washington, D. C.

We, the undersigned officers and enlisted men of the USAFFE, in grateful appreciation of the services rendered by the Philippine Chapter of the American Red Cross under the supervision of Mr. Irving Williams, Field Director, wish by this letter to express our gratitude.

The evacuation of the wounded soldiers from Manila by the Red Cross prior to its occupation by the enemy was instrumental in preserving the lives and health of the undersigned.

The document bore the signatures, rank, and home addresses of 210 of the Mactan’s patients all of them except those who had died or were too sick even to write their names. The addresses represented almost every state in the Union and every province in the Philippines.

Diary of Francis Burton Harrison:

January 6, 1936: completed entry

January 14, 1936: completed entry

January 16, 1936: completed entry

Diary of Diary of Basilio J. Valdes:

December 30, 1941: added links

|

| From Malacanan |

December 24, 1941: Philippine Army Chief of Staff and Secretary of National Defense, Secretary of Public Works and Communications and Secretary of Labor Basilio J. Valdes, and Executive Secretary Jorge B. Vargas, watch as President Manuel L. Quezon administers the oath of office to Chief Justice Jose Abad Santos, who also became Acting Secretary of Justice & Acting Secretary of Finance; witnessed by Jose P. Laurel and Benigno S. Aquino, in the Social Hall of Malacañan Palace. A few hours later the government evacuated to Corregidor, where the seat of government was transferred. Behind Quezon can be seen the Rest House (now Bahay Pangarap) across the river in Malacañang Park.

The Philippine Diary Project has several entries for this and the next day, covering different facets of life:

Basilio J. Valdes: December 24, 1941 begins his day at 8 am with a Cabinet meeting; on December 25, 1941, he recounts midnight Mass in Corregidor.

Ramon A. Alcaraz: does escort duties as a Q-Boat captain, on December 24, 1941.

Fr. Juan Labrador, OP, a Spanish Dominican, tries to piece together the information he has in UST for December 24, 1941. He is better informed than most.